After receiving the book “Arabic for Designers. An inspirational guide to Arabic culture and creativity” by Mourad Boutros, I was able to dive deeper into the importance of Arabic as a language, its historical background, as well as its cultural context. In this post I will summarize my findings from studying the introduction and the first chapter of the book.

The importance of understanding another culture

When trying to either work for a client of different cultural background, or trying to target the market of another culture, doing research to understand said culture is essential. If one ignores this step in the process, the whole project might turn into a disaster. In case of Arabic, people have made fundamental mistakes in the past, such as not taking into account that the language is not read from left to right, but actually the other way around. (cf. Boutros, 2017, p. 7)

Even as cultures today are merging and ever-changing, core elements and beliefs of cultural and national identities remain unchanged. When companies or individuals try to appeal to their target market, these long-established tendencies can not be ignored. An example of a failed attempt to reach a market with a different cultural background is Google. The search engine is still not the go-to choice for most users in Japan, since they tried to conquer the market with the same visual identity that worked for Americans and Europeans. However, the taste of Japanese internet users is different – they enjoy complex websites, decorated with texts and graphics, not the simple and clean look of Google. Furthermore, they also made major mistakes when introducing Google Maps to the Japanese market. The company made major mistakes, such as taking pictures of people’s backyards, which goes strictly against the country’s values of privacy. They also ignored the importance of public transport in Japan and directed people to a town’s geographical centre, instead of their bus or train stations. There were also inaccuracies in the historical maps, which led to disfavour towards Google from the Japanese. (cf. Boutros, 2017, p. 11)

The origins of the Arabic language

Together with Aramaic and Hebrew, Arabic belongs to the Semitic languages. Arabic is historically the last of the Semitic scripts, which are all read from right to left. The language spread throughout the world along with the religion of Islam and can be divided into two general groups: Classical Arabic and Modern Standard Arabic. The first is the language of the Holy Qur’an and pre-modern texts, the second is the language of media and most scholarly and literary texts. Arabic consists of 28 consonantal signs (three are also used as long vowels). Due to the tradition of passing down poetry and literature orally, written text was not widespread until the beginnings of Islam. Therefore, each calligrapher had his own style and no explicit rules existed. The shape of script held just as much meaning as the content, as the language relied heavily on its visual appearance to convey meaning. There is a common agreement among scholars, that the Arabic script had its origins in the Nabataean script dating from the 3rd century. It took another four centuries, until the 7th century, that written words became of importance. (cf. Boutros, 2017, p. 22)

The influence of Islam

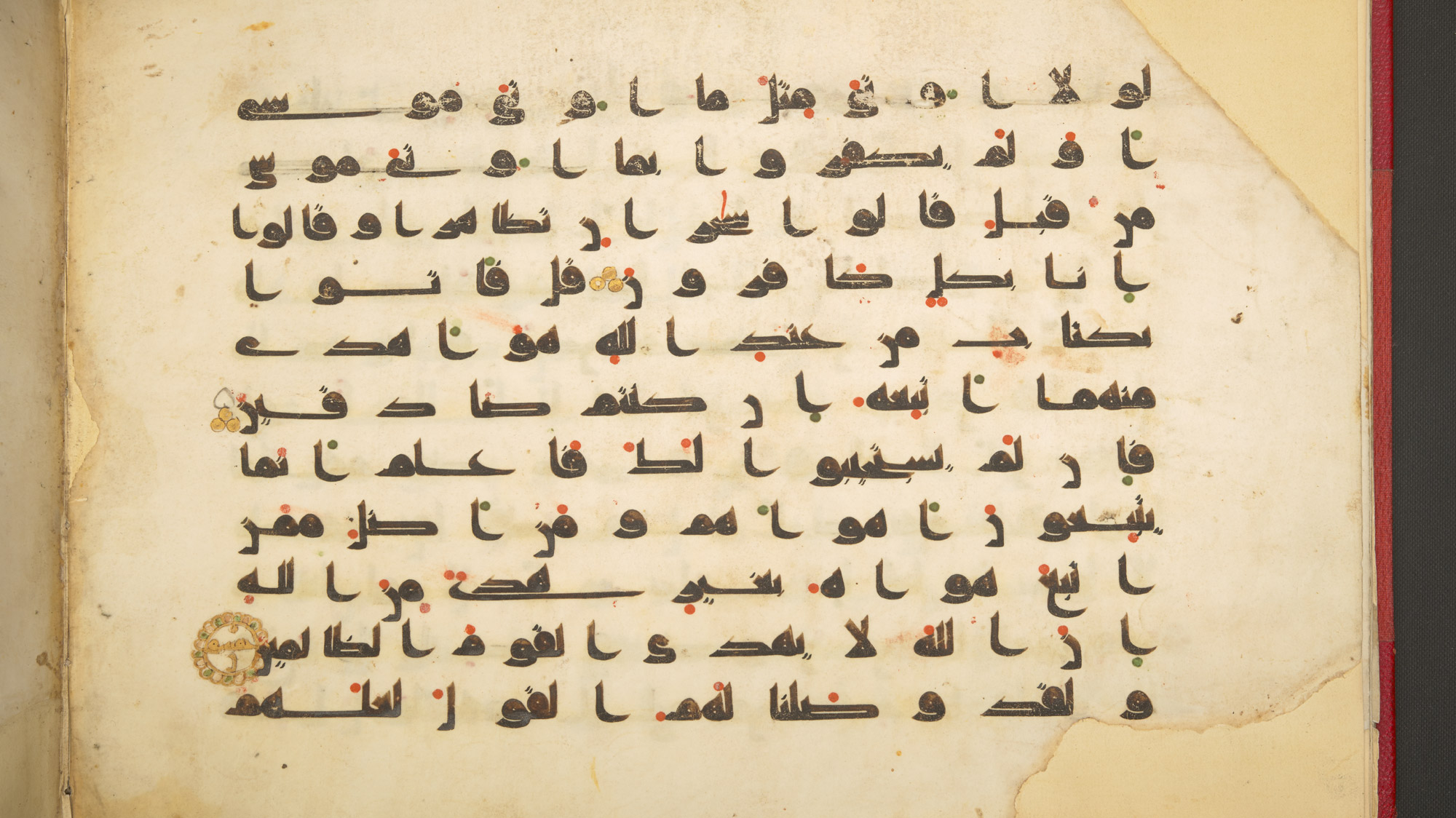

Muslims believe that Angel Gabriel revealed the Holy Qur’an to Muhammad between the years AD 610 and 632. They also believe, that while other holy texts such as the Bible or the Torah have been misinterpreted or forgotten, their Holy Qur’an is the embodiment of perfection. This created the need to capture every single word of the holy text in exact detail and therefore only relying on memory was not sufficient anymore. Islam heavily influenced the devlopment of Arabic calligraphy – it was transformed, improved and beautified. The reason for the aesthetic development of the script was to make it worthy of transmitting God’s divine message. Calligraphy also served as a tool for articistic expression, since figurative art was banned under strict interpretations of Islam. In 651 the first copies of the Holy Qur’an were written in two local variants of Jazm, Mecca and Medina. Soon they were superseded by Kufic, which got its name from the town Kufa located in Iraq. In the early history of Arabic writing, 150 different types of the Kufi script existed, leading to a large amount of variation. Arabic used to be written without any diacritic points, until the language’s development of inserting diacritic points to mean different things depending on the positioning. They were added in the form of red dots and strokes: On the top it stands for the sound ‘a’, on the letter itself for the sound ‘ou’ and below the line for the sound ‘e’. The introduction of diacritic points greatly helped non-Arabic speakers to understand and pronounce the phonetics properly and to read the Holy Qur’an. This process was therefore called Ta’jim, which comes from the word Ajam, meaning non-Arabic speakers. (cf. Boutros, 2017, p. 25)

The development of Arabic script

With the spread of Islam, many cursive scripts were developed and became prominent. All of them vary in style, because of the scriptwriters’ individual tastes.

Nakshi

It is one of the earliest cursive scripts and became popular in the 10th century. Due to its high legibility it was used for copying the Holy Qur’an. Characteristics are the short horizontal stems and the almost equal vertical depth above and below the medial line. Today Nakshi is used for headings, subheadings and body text in newspapers, books or advertising and remains as one of the most widely used Arabic style.

Ta’liq

It was first developed in Persia during the 15th century and later spread to Turkey and the Indian subcontinent. It is characterized by its fluidity and the varying thickness of the strokes. Today it is still used for newspapers and magazines in Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan where handwritten calligraphy is still popular.

Diwani

Diwani is based on Ta’liq, but has less dramatic hanging baselines. It evolved in the 16th century in Turkey and there also exists a decorative version known as Diwani Jali, which is widely used for ornamental purposes.

Riq’a

Riq’a has its origins in the 15th century, but only became popular in the 19th century. It is characterized by thick round curves and widely used in Egypt today (in the form of Egyptian Rokaa, a wider and airier verion of the original).

Thuluth

Thuluth can be traced back to the 7th century, but did not become to prominence until the late 9th century. Its thin fluid lines are used for calligraphic inscriptions, titles and headings. (cf. Boutros, 2017, p. 26-27)

The Kufic script

In the 8th century, the Kufic script achieved a level of perfection. Therefore it was used to transcribe the Holy Qur’an and was the dominant Qur’anic script for more than 300 years. It is characterized by static rectangular lines, short vertical strokes and extended horizontal lines.

The calligrapher Abu ‘Ali Muhammad Ibn Muqlah standardized the major cursive styles and created a comprehensive system of calligraphic rules. He redesigned the letterforms by using three standard units for measurement: the rhombic dot, the Alif, and the circle.

Alif

The Alif is equivalent to the letter ‘A’ in the Latin alphabet and was a vertical stroke measuring between 6 and 8 rhombic dots. The number of dots varied according to the particular style.

Circle

The standard circle has a radius equal to the height of the Alif.

Rhombic dot

The rhombic dot is the same size as the tip of a bamboo calligraphy stick. (cf. Boutros, 2017, p. 28)

References

Boutros, Mourad (2017): Arabic for Designers. An Inspirational Guide to Arabic Culture and Creativity. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd