Last week, from March 23rd-25th, we had the opportunity to attend the OFFF Conference in Barcelona. The conference included a wide variety of speakers on topics from graphic and media design, entrepreneurship and business, to UX and interaction design. My colleagues and I had a great experience in a beautiful and welcoming setting. As a group, we also discussed many of the talks after, and found that quite a few had evoked strong reactions. I often found that the following discussion with my colleagues was almost more impactful that the talk itself.

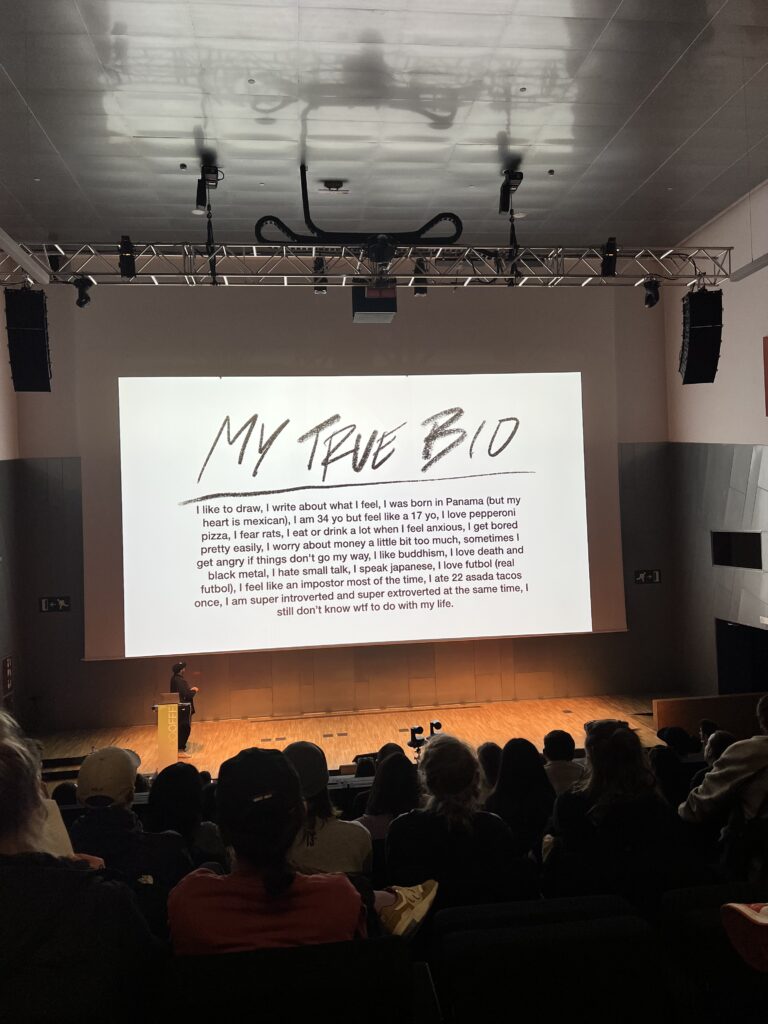

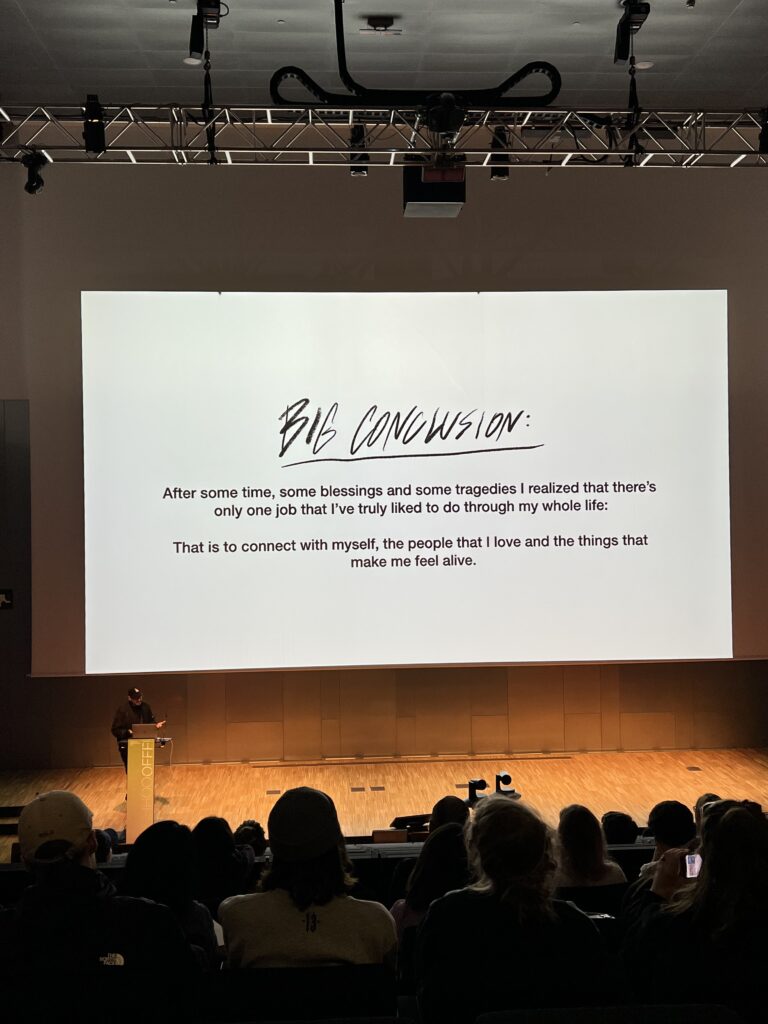

In one of these discussions, it was brought up that what was shared between many of the speakers was their insistence on the importance of experimentation. No matter how “successful” the designer was, they made sure to touch on past mistakes, moments of “selling out” in order to make ends meet, and their journey in trying everything and anything. They often also highlighted that they still don’t necessarily “know exactly what they’re doing”. Personally, I found these points very comforting. I really enjoyed the disarming transparency, particularly from Mexican designer and entrepreneur Rubén Alvarez. Alvarez began his presentation by sharing his “True Bio”, which included things like “I write about what I feel” and “Sometimes I get angry if things don’t go my way”. Alvarez then used his life story to explain to us how he came to be the designer he is today, including all the mistakes and failed ventures. This candor made Alvarez’s talk the most impactful for me. Some of the other posts discuss the disappointment many of us felt at talks given by more well known designers, who arguably abused the time and attention we gave them. In contrast, Alvarez was a human first and designer second.

I was very inspired by the honesty shown by many of the speakers at the OFFF Conference. It’s comforting when people share their mistakes and failures, as it makes us all less afraid to try and fail and try again. I would like to carry that thought with me as I move forward in my studies and career.