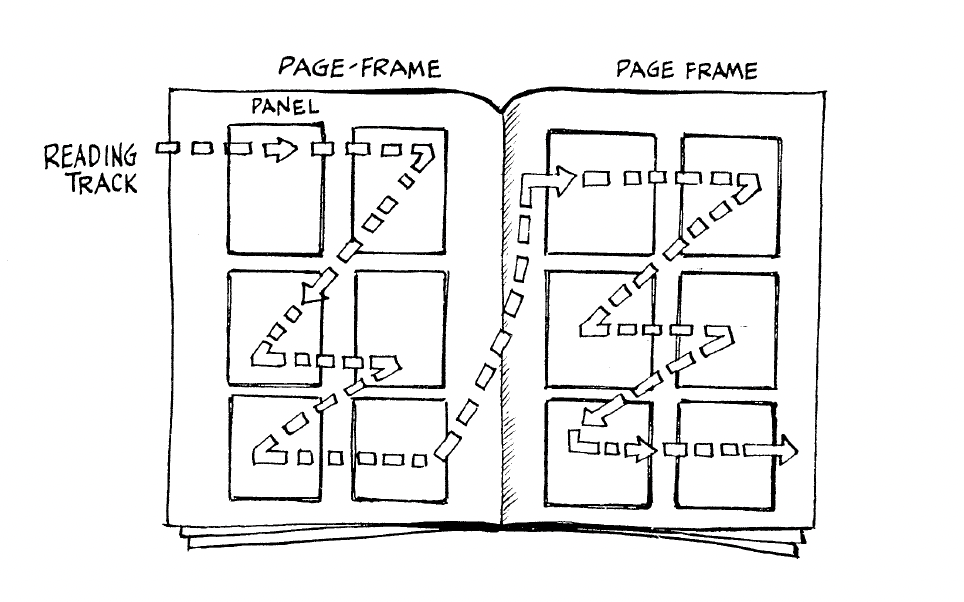

After looking into the basics of what to consider when creating any kind of narrative art and how to start thinking storytelling-oriented, in the past two weeks I researched the effect and meaning of one single image in narrative art and what to think about when creating one image for a narrative project with a sequence of images.

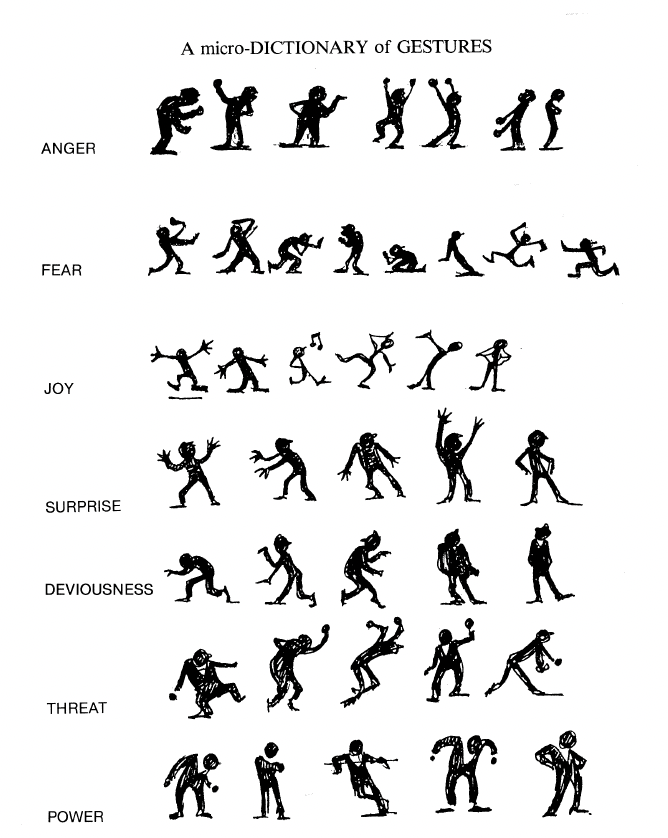

Catching the feeling of a figure or a scene

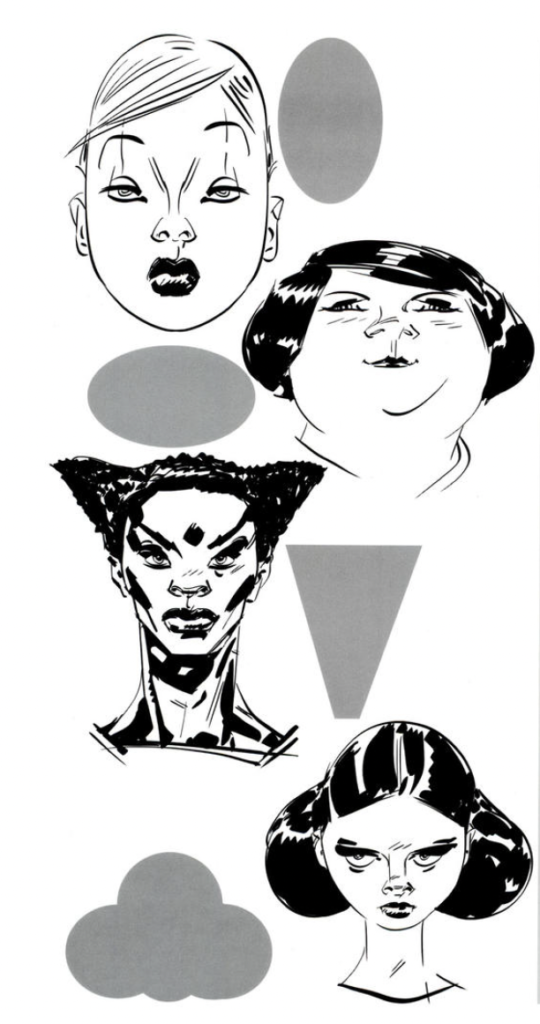

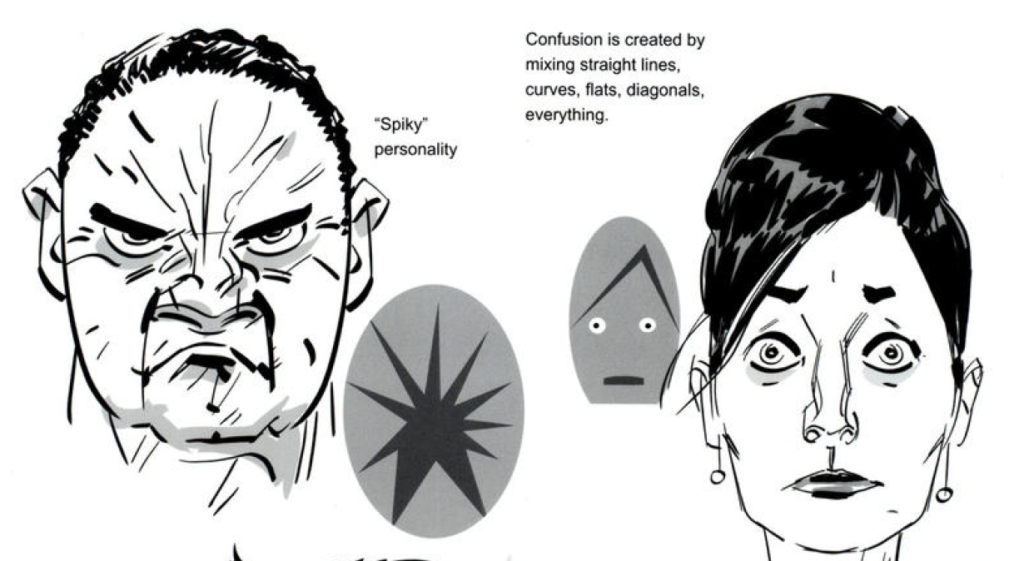

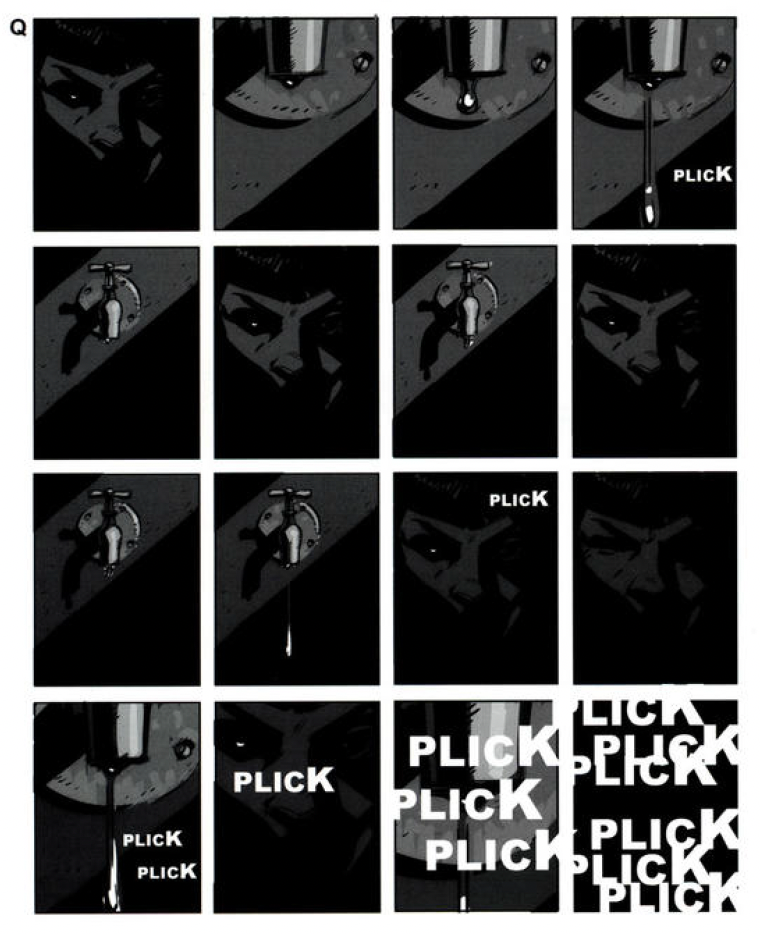

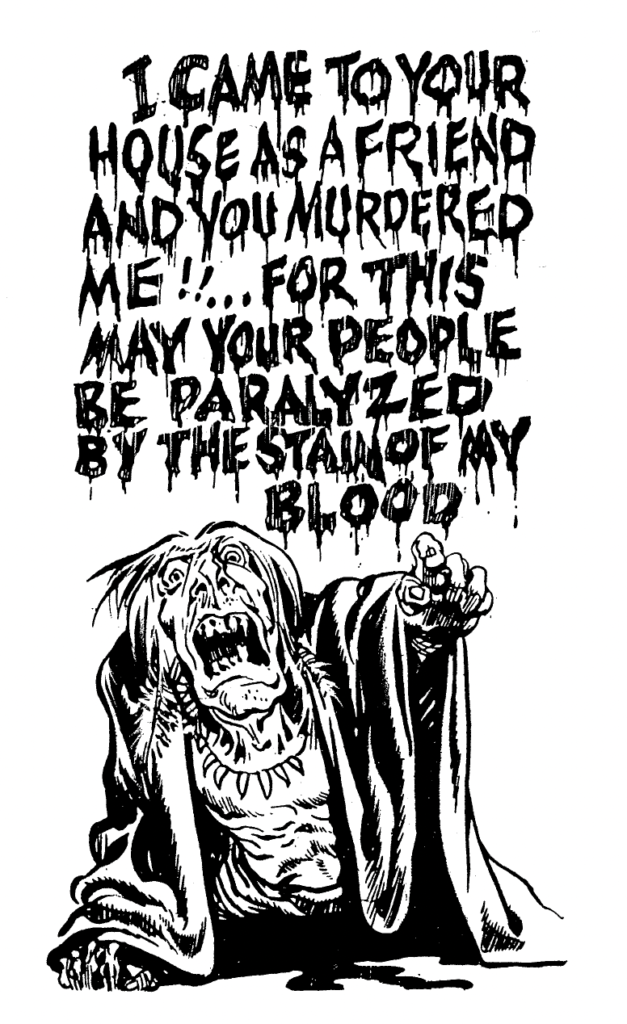

Mateu-Mestre points out that no matter how hard we try, we can never depict reality as it is. After all, our drawn landscape will be an image on paper and not a real-life scene, no matter how realistic it looks. Therefore, Mateu-Mestre explains his personal approach of trying to figure out the main characteristics and mood of the main object or figure depicted in a single image and recreating it in an abstract way. If we try to recreate every single detail of a scene we see in real life, our drawn image might show details but lose the overall mood that the real-life image radiates. He explains this concept using the face of a character as an example: instead of focusing on realistic details, he would try to make his vision blurry in order to see which features of the face stand out that give the face its characteristic expression and capture its mood. He would then focus on bringing attention to these “mood-giving” important features and not so much on details. The same principle applies to any kind of scene, not only to characters and faces. If we take a landscape as an example, we could try to make out what it is that gives this picture its atmosphere and then make these points stand out with their characteristic features in our drawing. (cf. Mateu-Mestre 2010: 18) In order to create strong impressions, we should also eliminate details that are not necessarily needed in the image (cf. Mateu-Mestre 2010: 21). This is also our natural way of seeing and perceiving things because we naturally only really perceive what information is needed by us at the moment and blend out the rest. For example, when we are searching for a friend in a crowd, we may not notice other details we see and only focus on recognizing the friends’ features. Understanding how selective vision works will also help us decide what might be important and unimportant in our scene. (cf. Mateu-Mestre 2010: 24)

So we look at things depending on what we require at the moment, and this is how we will select and highlight certain elements in our compositions as part of the visual message we want to deliver. Let’s frame and illuminate things in order to show what we need to show, how we need to show it, and, as much as we can, let’s crop out the rest.

(Mateu-Mestre 2010: 24)

Telling a story with lighting

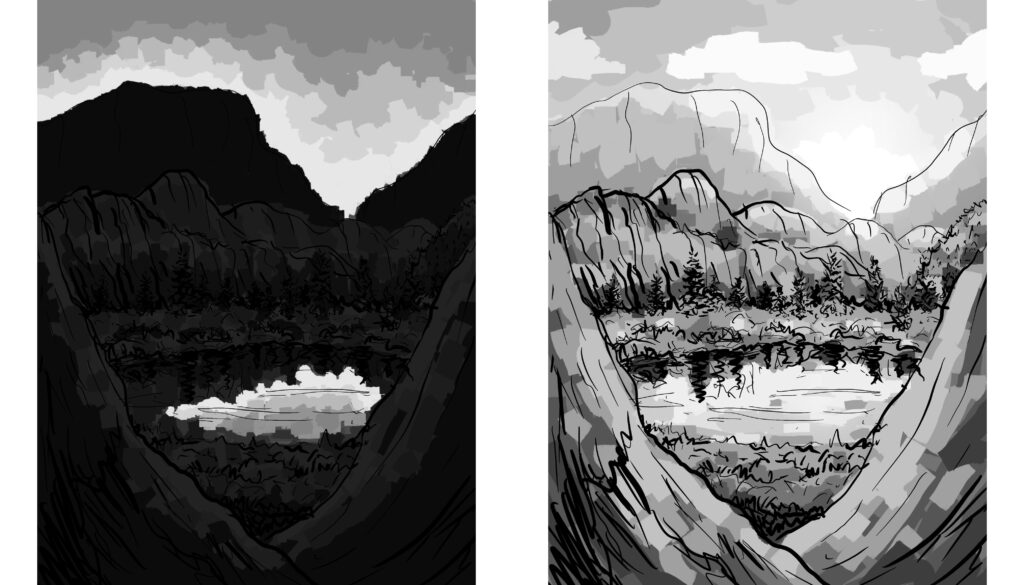

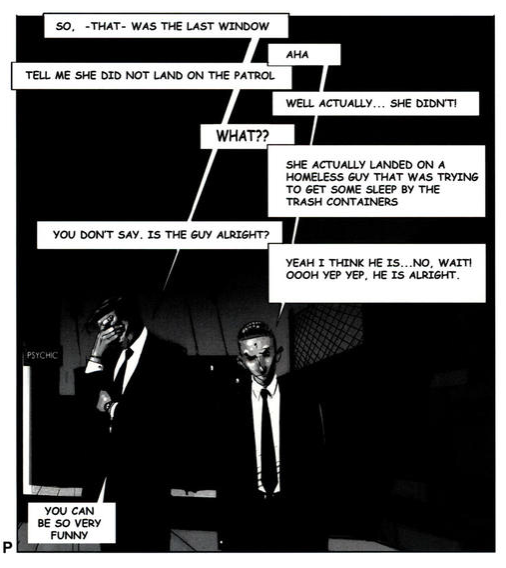

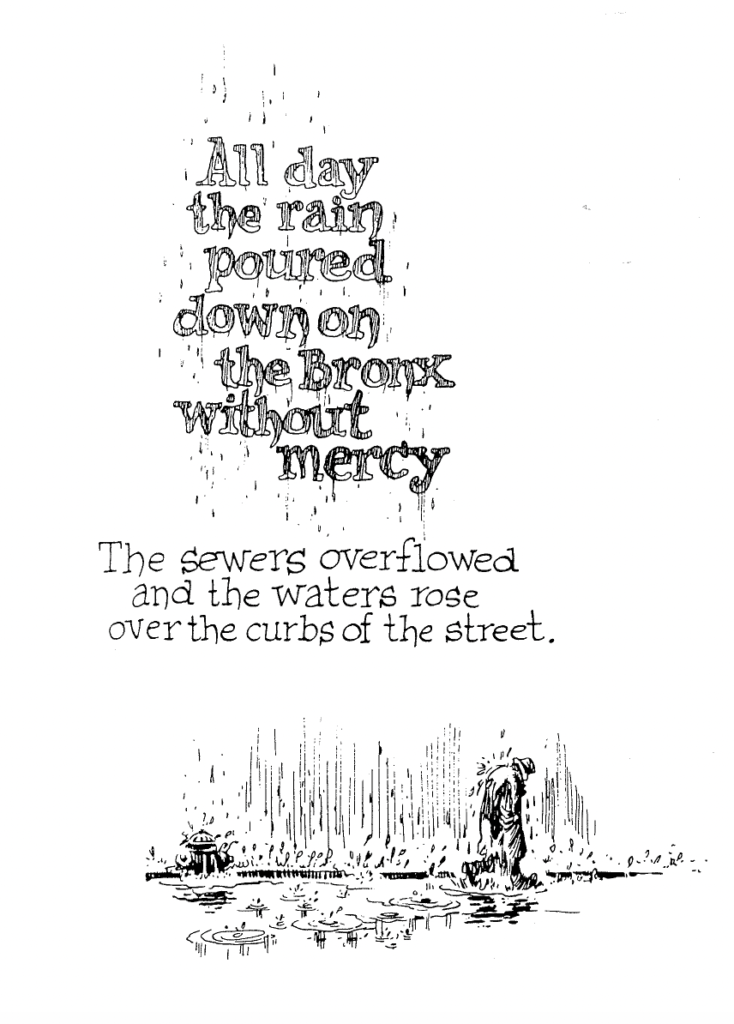

By changing the lighting, we can change the entire meaning and mood of a scene. If we take two identical locations, depict them and only change the lighting, the two pictures will tell a completely different story. Mateu-Mestre uses a room with minimal furniture items and windows as an example. If we depict this scene well-illuminated and show many details, such as what is outside the windows, the image may radiate a calm and secure vibe because the whole scene is visible – there is nothing hidden. We may create a comfortable, light-hearted mood this way. However, we can also depict this same scene in a horror setting. If we choose to depict this same room with very dark lighting, where, naturally, many details are hidden in the darkness and there is maybe only a faint outline of the furniture, the viewers will feel this dark and mysterious mood because many details are hidden and most of the scene is unidentifiable. (cf. 2010: 19)

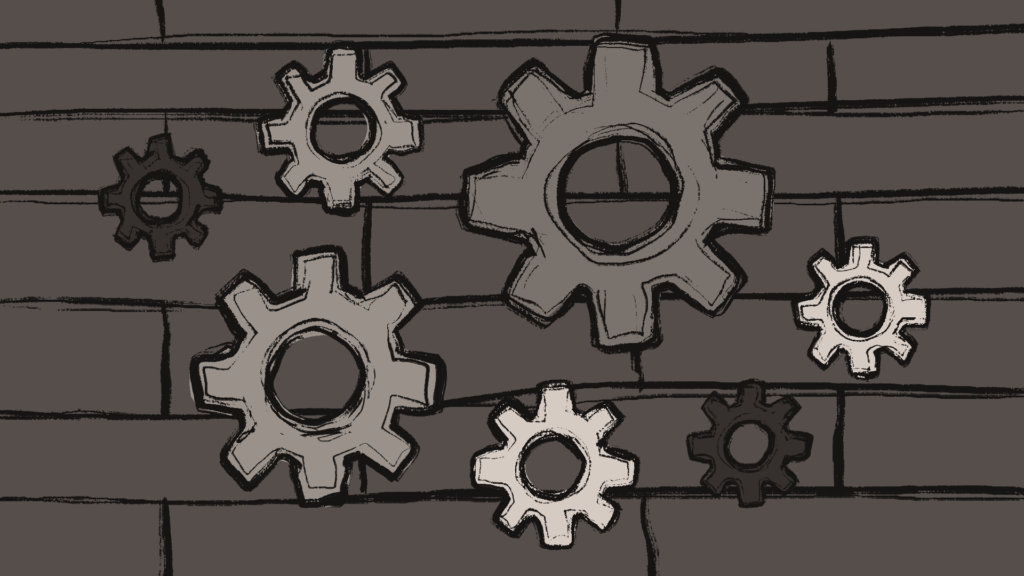

Mateu-Mestre also points out that it is good to not always focus on the outlines of objects as we do not perceive the outlines of objects in real life. Focusing on outlines might even stop us from drawing what we really want to express. If we stop concentrating on outlines and focus more on light and dark areas, we might be able to portray objects with more emotions depending on what we want to draw. (cf. 2010: 20)

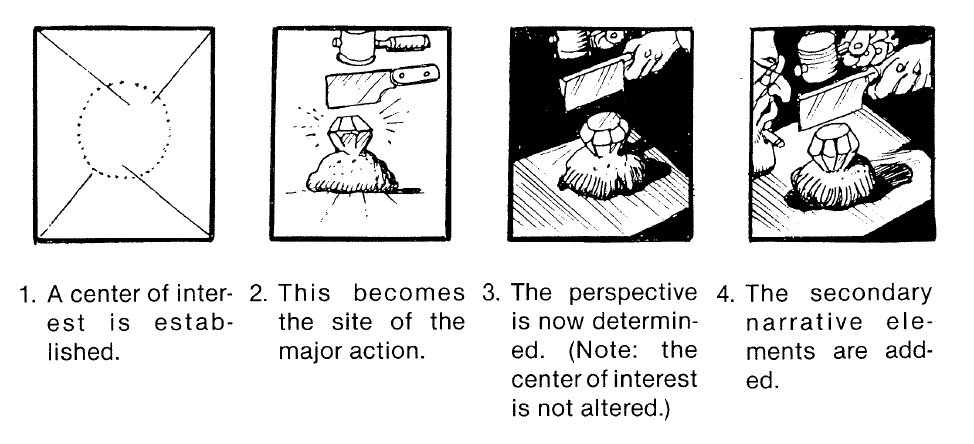

Now, how do we actually start composing a scene?

Mateu-Mestre explains in a helpful checklist what aspects to pay attention to when composing a single image for narrative art. However, he also mentions that these guides can and should sometimes be broken depending on what exactly we want to express. Sometimes, we might have a better idea for our specific image that conveys exactly what we want it to. (cf. 2010: 24)

Choice of shot

Long or wide shot: Usually, a scenery is depicted from far away to establish a scene and show a character in their environment.

Medium shot: Medium shots are used to still show the situation but crop out information that would disrupt the main message of the image.

Close-up: In close-ups, the features of the character are clearly visible. They are used when the reaction of the character is the most important thing in the image.

Extreme close-up: Extreme close-ups are good for when the audience should “become” the character and feel very close to them.

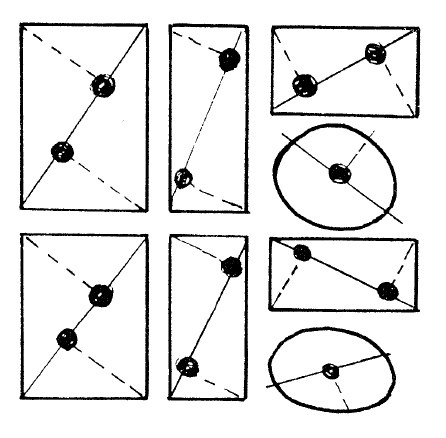

Positioning elements

Rule of thirds: Positioning our elements using the rule of thirds will help us to get interesting and natural-looking compositions.

Symmetrical images and center position: If we position the main elements in the center in ordinary scenes, the image may feel awkward. However, the center position can be used for epic and special moments.

Staying on the same side of the line: We should avoid axis jumps in order to not make the viewers lose the sense of direction and confuse them.

Lighting

We can use lighting to direct the viewers’ attention, to create mood and visual tension.

Lines and shape language

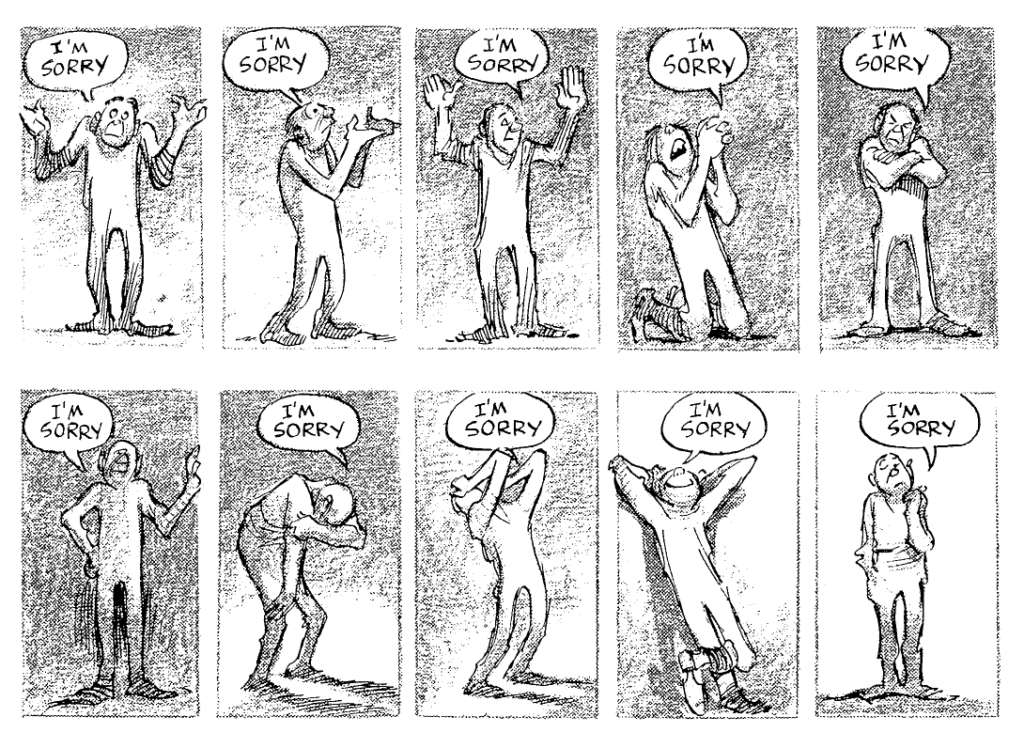

The shape of lines, whether they are actual lines or when we are just talking about the positioning of elements in a scene, influences how we perceive the image and what emotions we assign to it. Curved shapes and curves are generally perceived as more peaceful and kinder, while straight lines and diagonals seem more assertive and harsher. We can also use lines or the positioning of elements in some kind of line to direct the viewer towards something important and bring their attention to it. We should also pay attention to anything that accidentally catches the viewers’ attention, such as a weird positioning of some element, as this distracts from what we actually want to show.

Cutting in

Sometimes, we may need to show an establishing shot of a scene and, immediately after that, a close-up of some detail in this scene to point out this specific detail. When doing this, the detail should stay in the same position in both images.

Size difference

To create visually interesting images, we can portray the main objects or characters in the scene in different sizes. This makes an image seem more dynamic. We can also depict a more important subject bigger in size, or make it seem closer and therefore bigger to also bring attention to it.

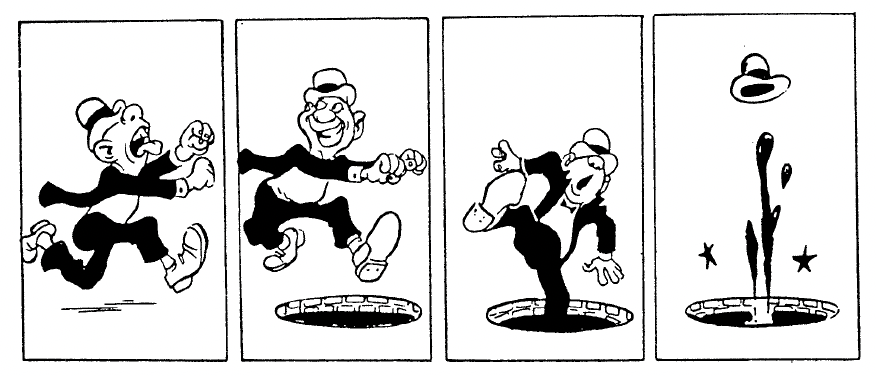

Perspective and direction

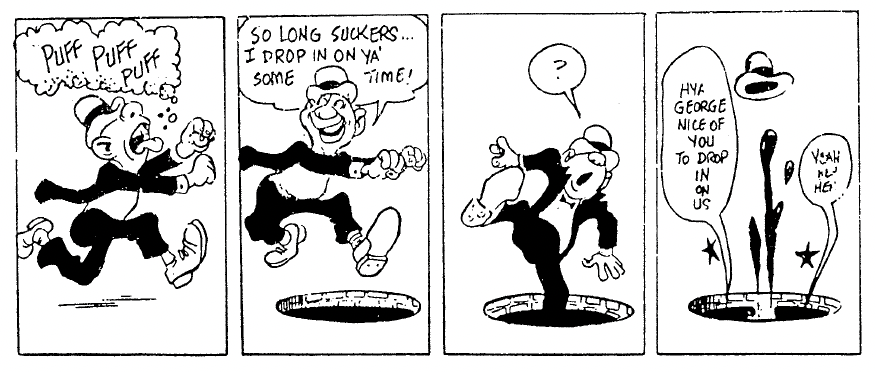

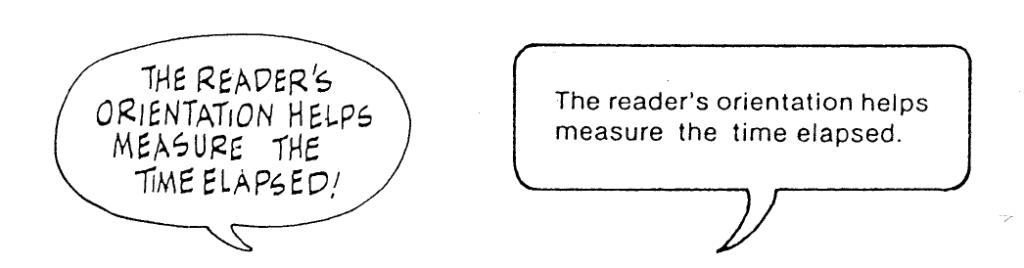

Because our eyes naturally follow lines and where they point, the vanishing point in an image will naturally be the center of attention. Where an important character in an image is looking at also affects the viewers’ attention, as we tend to look in the same direction in which we see someone looking in. Viewers expect that something important will be happening in that area. Our reading direction also influences how we perceive images. In our culture, we read from left to right. So, if whatever is happening in an image moves in the right direction, we tend to get the feeling that something positive is happening because it is the natural direction we are used to. If something seems to move from right to left, we automatically connect it to difficulty. To create a clear, well-flowing story, the direction in which a series of actions is happening should be the same in a sequence of images, unless we want to create a dramatic turn, then we can change the direction of actions to make use of this effect.

(All of the above “checklist”: cf. Mateu-Mestre 2010: 25-27)

Bibliography:

Mateu-Mestre, Marcos (2010). Framed Ink: Drawing and Composition for Visual Storytellers. Culver City, CA: Design Studio Press.