This post offers a summary of the history of animation and its different approaches and forms. What some call the earliest attempts at animation date back all the way to Grecian pottery, for its sequential drawings of movement and expressions, similar to single frames of a video. However, tools capable of actually producing what can be considered moving images did not exist until 1603, with the invention of the magic lantern. (cf. Masterclass 2021)

The Magic Lantern is believed to have been invented by Christiaan Huygens. Its use of candlelight in combination with illustrations on glass sheets made it the earliest form of a slide projector. These glass sheets were moved individually to project the first moving images. (cf. Magic Lantern Society)

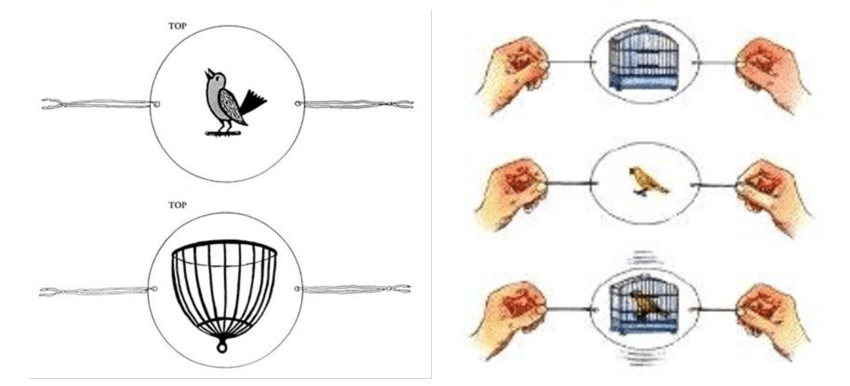

The Thaumatrope, introduced in the 18th century, was a disk with a picture on either side, held by two strings. Twirling and releasing these strings would spin the disk, showing what looked like both sides combined, caused by the phenomenon of persistence of vision. (cf. Masterclass 2021)

What is considered one of the first commercially successful devices is the Phenakistoscope, invented in 1832. It consisted of a flat painted cardboard disk that created the illusion of movement when spun (cf. Kehr, 2022), much like the sequential drawings of the aforementioned Grecian pottery.

The Zoetrope was the successor of the Phenakistoscope. It was based on the same principle as its predecessor, however it now came in cylindrical shape with small slits to look through, allowing multiple users to enjoy it at the same time. (cf. Masterclass 2021)

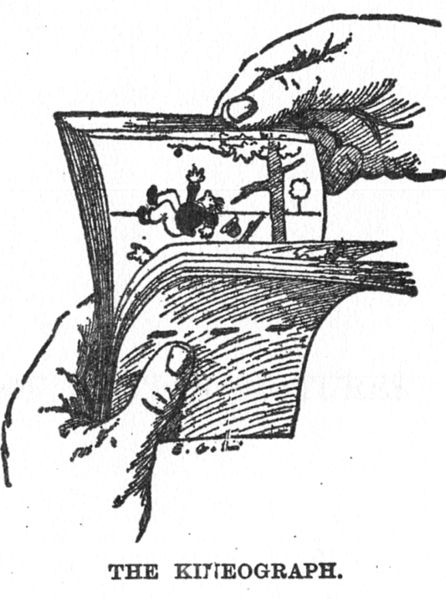

A different approach was taken with the Kineograph from 1868. It is also known as the flipbook, as it is a small book of again, sequential drawings, each page adding to movement of the previous one. Flipping through the pages quickly then resulted in a small animated scene. (cf. Masterclass 2021)

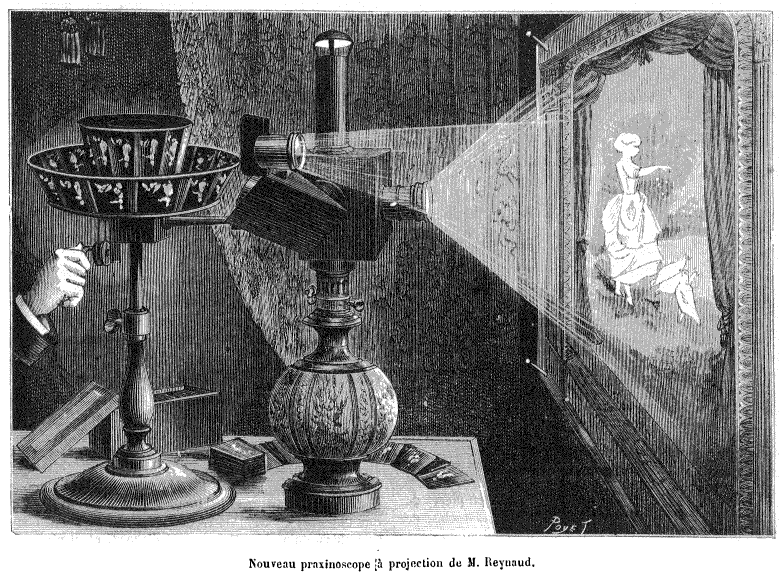

In 1876, the Zoetrope was improved upon again with the invention of the Praxinoscope. Émile Reynaud replaced the narrow slits with a mirror construction, allowing for a clearer and easier viewing experience by projecting it before an audience. (cf. Kehr, 2022)

All these early methods of animation even predate cinematography and film. Animation as we commonly understand it today is however intertwined with video. Although a clear first animated film ever is hard to establish and opinions differ, Émile Reynaud’s Pauvre Pierrot from 1892 is a good contender. It was the first to use a picture roll of only hand painted images instead of photographs. (cf. Masterclass 2021) Others that can lay claim to this title are J. Stuart Blackton with Humurous Phases of Funny Faces in 1906 or Émile Cohl with the creation of his animated protagonist in Fantasmagorie in 1908. (cf. Pallant 2011: 14)

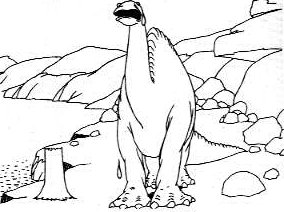

The basic principles established by these first works would then be built and improved upon in the upcoming years. Character animation was taken to a new level by Winsor McCay’s Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914, while John Randolph Bray released what is believe to be the first commercial cartoon in 1913 with Colonel Heeza Liar in Africa. This release was also the reason for the first cartoon serialisation. Not only series such as Felix the Cat (1919) profited from this established idea of a series of cartoons, but also Disney with its early works such as Mickey Mouse (1928) and the Silly Symphonies (1929) benefitted greatly from this. (cf. Pallant 2011: 14f)

A few years later Disney produced the first full-length animated feature film with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). It used traditional animation on a piece of transparent celluloid: Cel animation. This enabled artists to transfer parts between frames that were not moving. This greatly reduced the time of production, since every new frame did not have to be drawn from scratch, allowing background and other parts to be reused. (cf. Masterclass 2021)

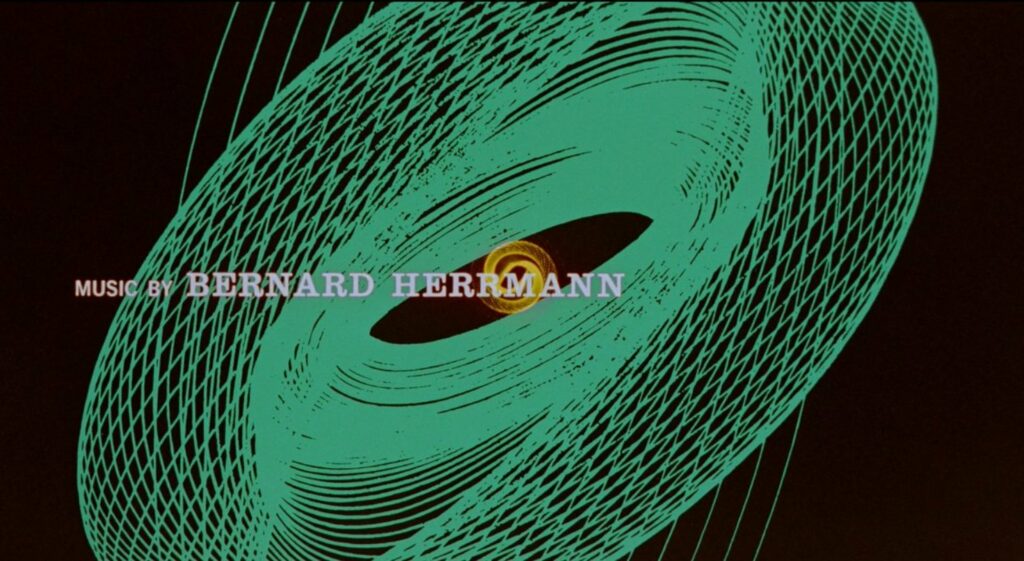

Around the same time, people began to experiment with animated computer graphics. Using custom devices and mathematics, John Whitney Sr. was able to produce precise lines and shapes on screen. This eventually led to him animating the opening sequence for the 1958 film Vertigo, making it arguably the first to use computer animation. (cf. Masterclass 2021)

In 1972, Edwin Catmull was only a student at the University of Utah when he created the world’s first 3D rendered film with his colleague Frederic Parke. It was constructed by scanning a mould of Edwin’s hand. This data was then traced by an analogue computer. (cf. HistoryOfInformation) Edwin would then continue to expand his knowledge and found Pixar Animation Studios. With Pixar, he released the first fully computer animated full-length film with Toy Story (1995) (cf. Kehr, 2022) This has fully paved the way for computer generated graphics to expand and continue to develop until today.

Sources

(1) Masterclass (2021): A Guide to the History of Animation [online] https://www.masterclass.com/articles/a-guide-to-the-history-of-animation [accessed on 13.01.2023]

(2) Magic Lantern Society (n.d.): About Magic Lanterns [online] https://www.magiclanternsociety.org/about-magic-lanterns/ [accessed on 13.01.2023]

(3) Kehr, Dave [Britannica] (2022): Animation [online] https://www.britannica.com/art/animation [accessed on 13.01.2023]

(4) Pallant, Chris (2011): Demystifying Disney: A History of Disney Feature Animation, New York, USA: Continuum

(5) HistoryOfInformation (n.d.): The First 3D Rendered Movie [online] https://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=4015 [accessed on 13.01.2023]

Figure Sources

Figure 1: Magic Lantern Society [n.d.]: Lantern Types [online] https://www.magiclanternsociety.org/about-magic-lanterns/lantern-types/ [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 2: Musa, Sajid/Rushan Ziatdinov/Carol Griffiths (2013): Introduction to computer animation and its possible educational applications: 177

Figure 3: Phenakistoscope (n.d): Phenakistoscope [online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Phenakistoscope_3g07690u.jpg [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 4: Zoetrope (n.d): Zoetrope [online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Zoetrope.jpg [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 5: Kineograph (n.d): Kineograph [online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Linnet_kineograph_1886.jpg [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 6: Praxinoscope (n.d): Praxinoscope [online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lanature1882_praxinoscope_projection_reynaud.png [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 7: Pauvre Pierrot (n.d): Pauvre Pierrot [online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pauvre_Pierrot.png [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 7: Gertie the Dinosaur (n.d): Gertie the Dinosaur [online] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gertie_the_Dinosaur_(retouched_frame).jpg [accessed on 14.01.2023]

Figure 8: Bernard Hermann (2021): Promotional Tweet [online] https://twitter.com/HerrmannMovie/status/1408907170029182976/photo/1 [accessed on 14.01.2023]